Arches and Zion national parks that covered my walls. After a few visits to Utah as a child and later as a college student on semester breaks, I found myself falling in love with the light, the mystery and the loneliness of southern Utah.

For many of my friends it was the same. Somehow we had been picked by the canyon country, and even though we were not aware of the immensity and complexity of the land that had cast its spell upon us, we began to explore its secrets. We were always amazed that it was wilder, bigger, more dangerous and more beautiful than we could have imagined

The maps told us a few things, but they were just rudimentary guides.

Arches and Zion national parks that covered my walls. After a few visits to Utah as a child and later as a college student on semester breaks, I found myself falling in love with the light, the mystery and the loneliness of southern Utah.

For many of my friends it was the same. Somehow we had been picked by the canyon country, and even though we were not aware of the immensity and complexity of the land that had cast its spell upon us, we began to explore its secrets. We were always amazed that it was wilder, bigger, more dangerous and more beautiful than we could have imagined

The maps told us a few things, but they were just rudimentary guides.

Beyond the maps were deep, narrow canyons with frigid pools of water untouched by sunlight even in June. We found Anasazi Indian ruins and pictographs like the Sky Faces, ghostly white visages painted high above a canyon at the top of a narrow sandstone

Beyond the maps were deep, narrow canyons with frigid pools of water untouched by sunlight even in June. We found Anasazi Indian ruins and pictographs like the Sky Faces, ghostly white visages painted high above a canyon at the top of a narrow sandstone

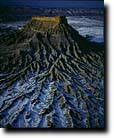

fin. On the craggy summit of Mount Ellsworth in the Little Rockies Wilderness Study Area, we looked out in wonder over the familiar canyons and mesas unfolding in a full circle panorama.

About 10 years ago I began to take along a camera. One of my initial motivations was that I was often in country that had not, amazingly, been photographed much before. Desolation Canyon, for example, a gorge as deep as the Grand Canyon but located in central Utah, is little known outside the state. So far its buttressed walls and stone arches thousands of feet above the Green River have, unfortunately, escaped permanent protection as wilderness. My family and I traveled through this canyon recently on a series of perfect October days. It was a special journey warmed by the waning autumn sun

fin. On the craggy summit of Mount Ellsworth in the Little Rockies Wilderness Study Area, we looked out in wonder over the familiar canyons and mesas unfolding in a full circle panorama.

About 10 years ago I began to take along a camera. One of my initial motivations was that I was often in country that had not, amazingly, been photographed much before. Desolation Canyon, for example, a gorge as deep as the Grand Canyon but located in central Utah, is little known outside the state. So far its buttressed walls and stone arches thousands of feet above the Green River have, unfortunately, escaped permanent protection as wilderness. My family and I traveled through this canyon recently on a series of perfect October days. It was a special journey warmed by the waning autumn sun  and touched by golden cottonwoods around every bend. We saw no one in five days except a cowboy who waved wanly to us from the far shore.

Another river canyon, Westwater Canyon near Moab, is unparalleled for scenic beauty and river running excitement. It is also so little known that photo editors refused to believe that an image I had made several years ago of its river sculpted Precambrian rock was not the Inner Gorge of the Grand Canyon. After the photograph appeared on the cover of a national magazine, a prominent environmentalist made speeches maintaining it was taken in Arizona, not Utah. Even those who should know better sometimes haven't fathomed the variey and extent of the Utah wilderness.

This wilderness is also an integral part of Utah's famous national parks and monuments. Outside the bustling and sometimes urban atmosphere of Zion Canyon, narrow slot canyons sinuously make there way through Navajo Sandstone toward the Virgin River.

and touched by golden cottonwoods around every bend. We saw no one in five days except a cowboy who waved wanly to us from the far shore.

Another river canyon, Westwater Canyon near Moab, is unparalleled for scenic beauty and river running excitement. It is also so little known that photo editors refused to believe that an image I had made several years ago of its river sculpted Precambrian rock was not the Inner Gorge of the Grand Canyon. After the photograph appeared on the cover of a national magazine, a prominent environmentalist made speeches maintaining it was taken in Arizona, not Utah. Even those who should know better sometimes haven't fathomed the variey and extent of the Utah wilderness.

This wilderness is also an integral part of Utah's famous national parks and monuments. Outside the bustling and sometimes urban atmosphere of Zion Canyon, narrow slot canyons sinuously make there way through Navajo Sandstone toward the Virgin River.  One late October, Bruce Hucko, Glen Lathrop and I rappelled or way down one of these nameless passages with all our photographic equipmemt, including 4x5 cameras and a large wooden tripod.

At first the going was easy and

One late October, Bruce Hucko, Glen Lathrop and I rappelled or way down one of these nameless passages with all our photographic equipmemt, including 4x5 cameras and a large wooden tripod.

At first the going was easy and  we were sure we would make our destination, the Zion Narrows, in a matter of hours. Our progress was eventually stymied, however, by a huge lake or reservoir formed when a rockfall ahead dammed the canyon below us. With no jumars to climb out the way we had come, we were committed to continuing through the icy lake. We spent precious time constructing a makeshift raft to carry the camera gear, then began the long swim to the last available sunlight across the lake. There, shivering and hypothermic, we realized our time was running out. We had now reached a section where the walls stood only a few feet apart and icy water rushed on all sides of us. At one point, my tripod slid under the surface of a deep, frigid pool. After several dives in his wet suit, Glen came up with it and we continued. As darkness approached we were only a few hundred yards from the narrows.

But more obstacles confronted us. A huge pine had fallen in the narrow corridor, allowing passage over a 50-foot drop-off only on its wet, mossy back. With courage derived from large amounts of adrenaline and the thought that we were slowly succumbing to hypothermia, we rushed across the log with ease. There, in the darkness, was our final

we were sure we would make our destination, the Zion Narrows, in a matter of hours. Our progress was eventually stymied, however, by a huge lake or reservoir formed when a rockfall ahead dammed the canyon below us. With no jumars to climb out the way we had come, we were committed to continuing through the icy lake. We spent precious time constructing a makeshift raft to carry the camera gear, then began the long swim to the last available sunlight across the lake. There, shivering and hypothermic, we realized our time was running out. We had now reached a section where the walls stood only a few feet apart and icy water rushed on all sides of us. At one point, my tripod slid under the surface of a deep, frigid pool. After several dives in his wet suit, Glen came up with it and we continued. As darkness approached we were only a few hundred yards from the narrows.

But more obstacles confronted us. A huge pine had fallen in the narrow corridor, allowing passage over a 50-foot drop-off only on its wet, mossy back. With courage derived from large amounts of adrenaline and the thought that we were slowly succumbing to hypothermia, we rushed across the log with ease. There, in the darkness, was our final  rappel, through a cascading waterfall that dropped more than 100 feet into the black Virgin River narrows below. One by one we descended to safety, feeling our way slowly along the slippery rocks, drenched continually by the falls. In a half an hour, we were back to the paved narrows trail. No pavement had ever looked so good.

Appreciation for the Utah red rock country has flourished in recent years, but the vast Great Basin deserts have not received as much respect. My hope is that Utahns and others will become aware of the beauty and wilderness values of areas like the House Range near Delta. On its dizzying limestone cliffs bristlecone pines frame emerald Sevier Lake far below.

rappel, through a cascading waterfall that dropped more than 100 feet into the black Virgin River narrows below. One by one we descended to safety, feeling our way slowly along the slippery rocks, drenched continually by the falls. In a half an hour, we were back to the paved narrows trail. No pavement had ever looked so good.

Appreciation for the Utah red rock country has flourished in recent years, but the vast Great Basin deserts have not received as much respect. My hope is that Utahns and others will become aware of the beauty and wilderness values of areas like the House Range near Delta. On its dizzying limestone cliffs bristlecone pines frame emerald Sevier Lake far below.  Such otherworldly landscapes are common in the seldom-visited mountains and playas near the Nevada border.

Nothing, however, prepared me for the Bonneville Salt Flats, perhaps the easiest place in Utah to produce interesting photos. I once watched from the summit of Silver Island Mountains as peak shadows stretched for dozens of miles across the ivory expanses of the flats. In September I saw the limitless salt flats transformed overnight by rains into a huge, shallow inland sea.

Near the summit of a remote Great Basin range, after an all day hike, I photographed Utah's largest cave opening. Its huge arching dome of orange limesone, hundreds of feet high and wide, framed range after range marching into Nevada.

Such otherworldly landscapes are common in the seldom-visited mountains and playas near the Nevada border.

Nothing, however, prepared me for the Bonneville Salt Flats, perhaps the easiest place in Utah to produce interesting photos. I once watched from the summit of Silver Island Mountains as peak shadows stretched for dozens of miles across the ivory expanses of the flats. In September I saw the limitless salt flats transformed overnight by rains into a huge, shallow inland sea.

Near the summit of a remote Great Basin range, after an all day hike, I photographed Utah's largest cave opening. Its huge arching dome of orange limesone, hundreds of feet high and wide, framed range after range marching into Nevada.  No winds could reach the back recesses of the grand opening to remove footprints in the limestone dust of the cave, yet we found no sign of others having been inside.

The Wasatch and Uinta ranges are the home of some of Utah's finest designated alpine wilderness. In northern Utah's mountains I have often been an observer of the great storms that furiously attack these ranges. I once cowered in my tent during a violent summer storm in the Uintas as lodgepole pines snapped and fell all around me. The sickening cracks and inevitable crashes of the great trees were a frightening reminder of nature's power over not only me, but the seemingly unchanging mountains. At other times I have marveled at the Wasatch mountains' luxurious wildflowers and their fall color displays that rival any of New England.

No winds could reach the back recesses of the grand opening to remove footprints in the limestone dust of the cave, yet we found no sign of others having been inside.

The Wasatch and Uinta ranges are the home of some of Utah's finest designated alpine wilderness. In northern Utah's mountains I have often been an observer of the great storms that furiously attack these ranges. I once cowered in my tent during a violent summer storm in the Uintas as lodgepole pines snapped and fell all around me. The sickening cracks and inevitable crashes of the great trees were a frightening reminder of nature's power over not only me, but the seemingly unchanging mountains. At other times I have marveled at the Wasatch mountains' luxurious wildflowers and their fall color displays that rival any of New England.  Although public opinion polls continually show most Utahns favor wilderness protection for more areas in the state, Utah has lagged behind other western states in wilderness designation. There are many areas presently under study and designated as "Wilderness Study Area" and they offer "outstanding opportunities for solitude", in other words, wilderness, by the Bureau of Land Management, which overseas 22 million acres in Utah.

Although public opinion polls continually show most Utahns favor wilderness protection for more areas in the state, Utah has lagged behind other western states in wilderness designation. There are many areas presently under study and designated as "Wilderness Study Area" and they offer "outstanding opportunities for solitude", in other words, wilderness, by the Bureau of Land Management, which overseas 22 million acres in Utah.

I have photographed, hiked and boated in many of these areas, and their beauty and wilderness potential are the equal of anything on display in our magnificent parks. The Utah Wilderness Coalition Proposal for preserving the land, wildlife, rivers and forests of 5.1 million acres deserves the support of everyone nationwide, who loves the slickrock and the stillness, the great rapids and the ghostly bristlecones, the ancient ruins and the rushing trout streams. It's all here. Take a look.

I have photographed, hiked and boated in many of these areas, and their beauty and wilderness potential are the equal of anything on display in our magnificent parks. The Utah Wilderness Coalition Proposal for preserving the land, wildlife, rivers and forests of 5.1 million acres deserves the support of everyone nationwide, who loves the slickrock and the stillness, the great rapids and the ghostly bristlecones, the ancient ruins and the rushing trout streams. It's all here. Take a look.

This site and all images © Copyright 1995-1996 Tom Till Photography.

tillphoto@sisna.com.